Intergenerational connections etched on the walls of Tāhuna

Aukaha's Mana Ahurea team worked with mana whenua, Kāi Tahu artists, and Kā Huanui a Tāhuna to pull forth Kāi Tahu narratives and designs into the streets of Tāhuna Queenstown.

1 March 2024

The tenacity and strength of famous Kāti Māmoe ancestress Hākitekura is one of many Kāi Tahu pūrākau being celebrated on the streets of Tāhuna Queenstown.

Her legendary feat, plus the celebration of ahikaaroa and wāhi tīpuna, are depicted in visual artworks and titoka (composition) on 19 large precast concrete panels weighing between four and 11 tonnes being installed on the Beetham and Melbourne Streets retaining wall, adjacent to St Joseph’s Catholic church.

Hākitekura is a renowned wahine toa (heroine) who grew up on the banks of Whakatipu Waimāori (Lake Wakatipu) and was the first person to swim across Whakatipu Waimāori, Aotearoa New Zealand’s longest lake.

Aukaha, a mana whenua owned consultancy, was supported by a mana whenua expert panel to work with Kāi Tahu artists and Kā Huanui a Tāhuna (the Whakatipu Transport Programme Alliance, delivering capital projects on behalf of Queenstown Lakes District Council and Waka Kōtahi) to weave mana whenua narratives into stunning artworks.

The project is called He Pae Mauka - referring to the various mauka surrounding the location - Kā Kamu a Hākitekura (Cecil and Walter Peaks), Te Tapunui (Queenstown Hill), and Kā Tiritiri o Te Moana (Southern Alps).

Under the Design Lead of Keri Whaitiri (Kāi Tahu, Kāti Māmoe, Ngāti Kahungunu), Te Rūnanga o Ōtākou's Kāi Tahu reo expert, waiata composer and mana whenua panel representative Paulette Tamati-Elliffe (Kāi Te Pahi, Kāi Te Ruahikihiki, Te Atiawa, Ngāti Mutunga) worked alongside lead artist Jen Rendall (Kāti Kuri, Ngāti Rakiāmoa, Ngāti Waewae, Ngāti Irakehu) and Jen’s son, renowned musician Marlon Williams (Ngāi Tahu, Ngāi Tai, Tūhoe).

The team held a workshop with students from nearby Hato Hōhepa a Tāhuna / St Joseph's School, to explore wāhi tīpuna and pūrākau that had a strong relationship to the wall site.

Through waiata, composition and performance, and beginning with Kāi Tahu creation traditions, the students learned about Hākitekura, mahika kai, and the flora and fauna that used to cloak the whenua before colonial settlement.

“The artwork reflects our intergenerational connections to the inland area. There was a focus on our whakapapa to Hākitekura, who is a prominent figure in our history. Hākitekura is the daughter of Kāti Māmoe chief Tūwiriroa. Her name features in many place names of the area, referring to the occupation of her and her whānau in and around Tāhuna,” Ms Tamati-Elliffe says.

“It’s important we bring our cultural narratives to the forefront so our children can recognise themselves in the environment, and connect their knowledge of waiata, pūrākau and kōrero handed down through generations to the visual aspects of the built environment.”

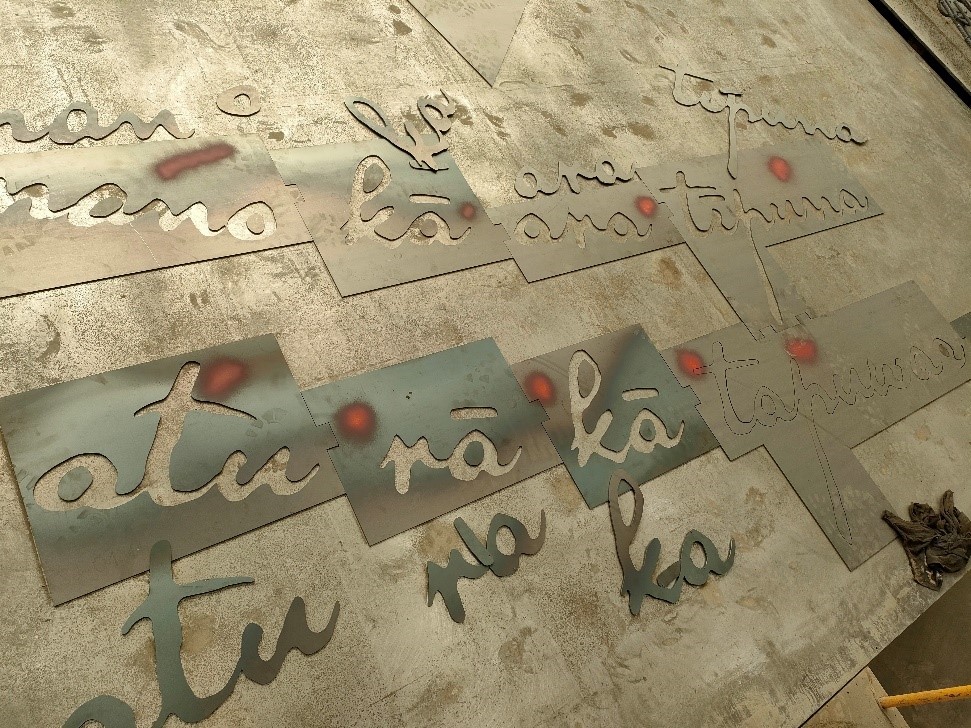

Kupu have been inscribed onto the retaining walls that speak to Hākitekura’s determination and strength, as well as her descendants’ long-standing occupation of the central inland area:

-

- Nāia te toa o Hākitekura! (Here is the victorious Hākitekura!)

- He ahikāroa, he ahitūroa, Te Ahi-a-Hākitekura (The continuous occupation, the permanent occupation, the enduring fire of Hākitekura)

- E, Te Tapunui! Kā noho āhuru mātau i tō marumaru ki te pa tūturu o Tāhuna (Oh Tapunui, we dwell in the traditional pā of Tāhuna under your protection)

- Tu tonu rā kā-kamu-a-Hākitekura. (The peaks of Hākitekura remain steadfast throughout time)

- He manomano kā ara tīpuna. Whāia atu rā kā tapuwae o rātou mā. (There are many ancestral pathways. We follow in their footsteps.)

Through her research of place names across Tāhuna, Ms Tamati-Elliffe says interpretations by English historians mistakenly recorded incorrect Māori names. One such example is the name ‘Kā Kamo o Hakitekura’ for the Cecil and Walter peaks (which translates to ‘the eyes of Hākitekura’).

Ms Tamati-Elliffe worked with rakatahi Māori (young Māori) first language speakers, who concluded that the word kamo, meaning eyes, was mistakenly written down for the word kamu, a term used for a pattern used in tāniko (Māori weaving) that uses triangular peaks on the boarder of clothing.

Those peaks, therefore, are more likely to refer to the Cecil and Walter peaks.

“It has taken this long for us to grow generations of reo speaking tamariki who can analyse these things through a different lens,” she says.

“This is what we believe it was in reference to. Jen has included that pattern, the border on the korowai and kākahu, referring to those significant practices of our ancestors in making traditional clothing, using natural resources, and looking to our environment for inspiration.”

Flora and fauna included in the artwork include Tī Kōuka (cabbage tree), Houhi (mountain lacebark), Southern Kōwhai and Kōtukutuku (tree fuchsia).

Tī Kouka was an important kai for enduring sustenance during long distance travel. Harvesting would take place in and around Central Otago during the summer, where hundreds of families would gather to make the kouru, a sweet fructose sugary substance that would be traded or used for travel.

On the same road, artist James York (Kāi Tahu ki Ōraka Aparima, Ngā Puhi) has designed Ahi Kā (ancestral connection and ongoing identity) concepts on further retaining walls.

Kāi Tahu traditions associated with Tāhuna, Whakatipu Waimāori and the wider area begin with the creation of the landscape associated with Te Kāhui Tipua (the old tribes) and the arrival of the Waitaha. Their leader, Rākaihautū, used his kō (digging stick), to dig out the inner lakes and light fires of human occupation within Te Waipounamu.

Waitaha remained in and around Whakatipu for generations, using the unique resources of the area including pounamu found at the head of the lake.

Kāti Mamoe followed, intermarrying with Waitaha, and established settlement. As a result of conflict along the east coast with the recently arrived Kāi Tahu, a group of senior Kāti Mamoe chiefs established pā and kāika in and around the Southern Lakes, including Tūwiriroa at Tāhuna.

Kāti Mamoe used the area as a refuge as well as using pounamu and the abundant mahika kai resources on offer. They remained until the late 1700s when interactions, conflicts and ultimately alliances with Kāi Tahu developed. After this time Kāi Tahu continued to utilise the area for mahika kai, which changed dramatically with the arrival of European settlers from the early 1800s.

“That whole whenua is our tribal estate and going up there is part of our lifestyle. We have named these places, these mountains after our ancestors, after our experiences and our knowledge systems and we are maintaining those connections intergenerationally,” Ms Tamati-Elliffe says.

Media Contact:

Dani McDonald

Dani@aukaha.co.nz

The story of Hākitekura

After watching other young women attempting to outswim each other, Hākitekura decided that she wanted to outdo them. She used a kauati (stick used to start fire) from her father, and a bundle of dry raupō for kindling. The next morning, Hākitekura set out from Tāhuna. With the kauati and raupō bound tightly in harakeke (flax) to keep them dry, she swam across the lake in darkness, with the bundle strapped to her. When Hakitekura landed on the other side of the lake, she lit a fire that blackened the rocks. This place became known as Te Ahi-a-Hākitekura, meaning “The Fire of Hākitekura”.